Myth busters #2 - All metal gas and water pipes must be bonded to the main earthing terminal

Sometimes we do tasks without giving things too much consideration, often because we were taught to do something a particular way and never really thought about (or forgot) the reasons why. A good example of this is Regulation 411.3.1.2 of BS 7671: 2018, which requires that:

“In each installation main protective bonding conductors complying with Chapter 54 shall connect to the main earthing terminal extraneous-conductive-parts including the following:

Water installation pipes

Gas installation pipes

Other installation pipework and ducting

Central heating and air conditioning systems

Exposed metallic structural parts of the building.”

Therefore, is it true to say that all gas, water, aircon pipes and ducts along with structural metalwork should be bonded? The answer is no, and the reason is because they might not be extraneous-conductive-parts. As with many British Standards, the requirements are often written in a particular way to eliminate ambiguities; if you talk to any British Standards committee member they will usually be able to regale tales of sitting around the table for hours just to write a single sentence which is not only technically correct, but also one that everyone can agree on. To the casual reader though such carefully crafted language can, on occasion, have the opposite effect.

In the above Regulation, it states that conductors “shall connect to the main earthing terminal extraneous-conductive-parts” and then goes on to list examples including gas and water pipes. But if an item of metal is not an extraneous-conductive-part, Regulation 411.3.1.2 does not apply. It follows that if an air handling duct, gas or water pipe does not fulfil the definition of an extraneous part, then it won’t need protective bonding.

The advent of plastic plumbing caused some confusion over the application of this Regulation in practice, so in the 18th Edition it was modified to include the statement “Metallic pipes entering the building having an insulating section at their point of entry need not be connected to the protective equipotential bonding.” And the reason for that is because with a plastic insert, the electrical continuity between the mass of Earth and the metallic pipework in the installation has been broken and so the pipework is no longer considered an extraneous-conductive-part.

IET Guidance Note 8 covers earthing and bonding and in Part 6 it goes on to explore the definition of an extraneous-conductive-part. Part 2 of BS 7671 defines one as “A conductive part liable to introduce a potential, generally Earth potential, and not forming part of the electrical installation.”

Even with such a definition, it is sometimes difficult to establish what is, and what is not an extraneous-conductive-part. To assist in making this decision, Guidance Note 8 encourages the reader to analyse the definition by breaking it down into three discrete parts:

- a conductive part;

- liable to introduce a potential, generally Earth potential; and

- not forming part of the electrical installation.

Given that many modern buildings now have plastic services (gas, water, sewage etc.) the need for protective bonding is reducing but may still be necessary.

To be sure, it is always wise to check and Guidance Note 8 gives some methods for achieving this. In essence, the intention behind bonding extraneous-conductive-parts is to limit the potential difference across the body when a fault occurs in part of the electrical system.

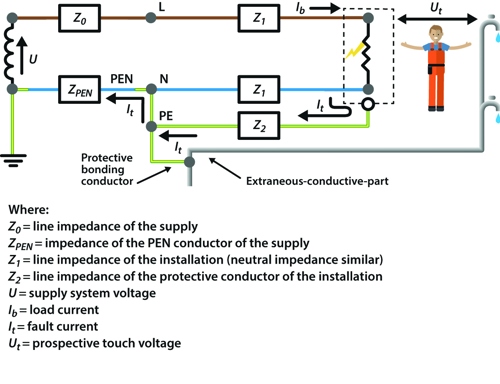

Take for example an earthed appliance (such as a kettle) on the worktop next to a metal kitchen sink with metal plumbing connected to a buried metal cold water main as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Example of touch voltage between earthed metalwork and faulty appliance in a TN system (Reproduced from Commentary on the IET Wiring Regulations)

The kitchen sink and taps are likely to be at Earth potential, i.e. 0 V. Without any protective bonding, if there was a fault with the kettle and a person had one hand on the sink when they grabbed the kettle, itself in a fault condition, then a potential difference will be present across the person leading to an electric shock.

If the water pipe is connected to the main earthing terminal (to which the case of the kettle is also connected) then the two are effectively joined together and the potential difference between them will be negligible and the shock risk will be mitigated.

It also follows from this that the extraneous-conductive-part must be accessible and that it is possible for someone to be in contact with it and a part of the electrical installation under fault conditions. If the conductive part is inaccessible and will be for the life of the installation and there is no opportunity for simultaneous contact, then it may not be part of the electrical installation and hence not an extraneous-conductive-part.

Guidance Note 8 details some simple continuity tests that can be conducted to check whether a part is extraneous or not, depending on the protection installed in the installation.

Figure 1 shows an inappropriate application of this requirement. In this installation, the gas bottles are connected to a changeover valve via rubber hoses, so the changeover valve is quite isolated from the bottles and the mass of Earth, as is the gas pipework connected to it (in this example, the gas pipe is fed straight into a boiler the other side of the wall).

Other examples of items that are commonly bonded but are unlikely to require it include metallic window and door frames (except those in metal buildings), cable tray or basket which is not used as a protective conductor, kitchen sinks where plastic plumbing is in use, IT equipment racks and doors and so on. It is easy to think that bonding such items won’t hurt even if it is not necessary, but remember that by doing so it gives rise to the possibility of exporting fault voltages throughout an installation; it could transpire to be more dangerous than not bonding in the first place.

Generally, the consideration for extraneous-conductive-parts are where they will introduce Earth potential into an installation, but that may not always be the case. Telecoms, data or control circuits derived from other supplies or buildings for example could introduce other voltages into the electrical installation and hence may present a shock hazard under fault conditions, so they should also be considered.

Finally if earthed conductors from another electrical system are introduced into an installation (such as a supply from one building into another) the joining of them may require special consideration – see Regulation 411.3.1.1 which requires them to be joined together and also regulation 542.1.3.3, which concerns the maximum current conductors may experience. If this would be problematical (e.g. for interference or safety reasons) then other measures may be required, such as preventing simultaneous access using, for example, insulation or enclosures. Determination of the maximum current that might flow when interconnecting earthing systems of different installations may require knowledge of potential fault conditions on any HV networks supplying the installations: BS EN 50522 and BS EN 61936-1 contain useful information on this subject.